As market economies become more expensive and predatory, Stephanie Rearick is showing that it’s entirely possible to meet people’s needs effectively through care and cooperation, through a kind of alternative social economy.

For more than twenty years, Rearick has championed mutual aid and cooperative economics through such projects as the Madison Mutual Aid Network Cooperative and the Dane County TimeBank, both of which she founded. Rearick also works internationally through Humans United in Mutual Aid Networks, a global network of networks dedicated to building mutual aid economy.

Rearick is keenly aware of the pressures that the formal economy exerts on people. Government budget cutbacks, corporate price gouging, engineered dependencies, trade tariffs, and inflation all contribute to our precarity.

This state of affairs has quickened interest in mutual aid as a practical strategy. Rearick reports that a recent online webinar on mutual aid hosted by the resistance group Indivisible attracted some 5,000 attendees.

It’s almost as if thinking big about different social logics has become fashionable – or alternatively, as a serious survival strategy. “I often say that the best part of my job is helping people see we can afford to dream better,” Rearick told Shareable.net.

To learn more, I recently interviewed Stephanie Rearick on my Frontiers of Commoning podcast (Episode #69). It was a brisk immersion in the fiercely resourceful, committed world of mutual aid and cooperative economics that works at local, regional, and international levels.

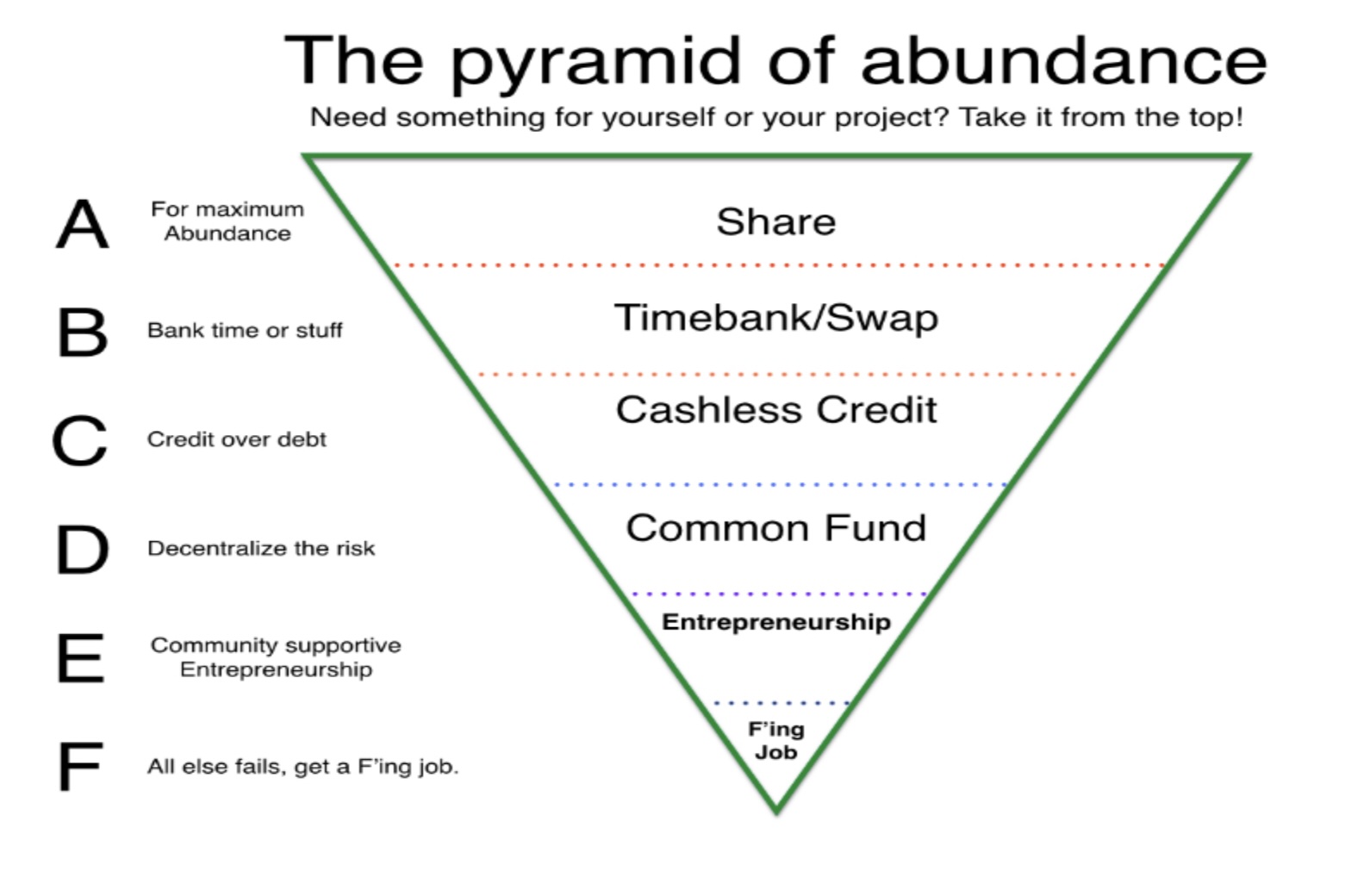

Mutual aid prioritizes social cooperation and then dreams about how to develop better organized systems to encourage it. To illustrate its priorities, Rearick’s website features a “pyramid of abundance” -- an inverted pyramid that lists several tiers of activities for meeting needs.

The first tier of abundance is “sharing,” followed by “timebanking” or “swaps.” If necessary, a person can rely on a cashless mutual credit system to meet needs, or participate in a common fund, or pool of money, to meet needs. A lower priority is “entrepreneurship,” followed by the very lowest priority, “when all else fails, get a F’ing job.”

“What we want to show people is that it's not rocket science,” said Rearick. “It's really as simple as making some different choices about how you meet your own needs.”

Mutual aid is often perceived as charity -- neighbors giving groceries to people in need, volunteers taking the elderly to doctors’ appointments. Rearick has no problems with socially minded charity, but she emphasizes that mutual aid is really about building community systems. The point is for people to connect meaningfully with each other and work together to meet everyone’s needs. “Mutual aid is mutual,” said Rearick, “and the mutuality and reciprocity built into it are what enable it and cause its social dynamics [of care and support] to ripple out.”

Timebanking is a great example, she noted, because it works on the premise that anyone has something valuable to contribute. People should not be defined by what they may lack – money, education, a home – but by their willingness and ability to help.

Timebanking is a time-barter exchange that invites people to declare what skills and expertise they can offer to others. The project database helps connect people with others who need those talents. But it’s not a cash purchase of services, but an exchange of time -- one hour of donated time that someone else can use by offering their own time to others. The unit of exchange is one hour.

By bringing together more than 2,800 people to share their time with others, Dane County TimeBank has not just met people’s needs – for childcare, lawn-mowing, healthcare support, rides – it has built a community of mutual support.

It's a simple concept that has had many fascinating extensions, each of which relies on committed social engagement, without money. “Time banking is a took to make visible the real wealth of our community,” says Rearick.

Once organized, a community can catalyze a lot of follow-on activity. For example, the Dane County TimeBank once made a loan for someone to get a food cart and start a business, an initiative that worked only because the community stood behind the loan.

Another timebanking spinoff that Rearick is developing is “neighbor care teams” whereby a team of people convene around someone who's very ill or homebound. The goal of the Health + Care Network is to make sure that the person can get the food, medicine, transportation, and household chores that they need done. This approach, already successful in Philadelphia, shows great promise in filling holes that the formal healthcare and social services system doesn’t meet.

Another timebanking spinoff is a “restorative justice youth court” pioneered in Washington, D.C., by the late timebanking founder Edgar Kahn. Young people who get into trouble with the city can come to a circle, or jury, of their peers trained in restorative justice. They learn more facts, adjudicate the offense, and recommend suitable action.

The jury of young people don't just find out what happened, but what's going on in an offender's life with their family, in their neighborhood, at their school. They learn about the person’s strengths and interests, and about what needs are not being met that might lead them into antisocial behaviors. And then they would create an agreement with them.

“So if a kid was stealing, they might need to take classes in employment skills and money management, or if they were lashing out in anger, they would need to learn some nonviolent healthy communication skills. Instead of just working to not criminalize people and not incarcerate people,” said Rearick, “you need to work on building the community supports that create public safety and meet people's needs.”

This approach “just changes the whole dynamic. Instead of getting into trouble from an adult, you're getting understood by other young people and then you're being connected in your community. That was huge.”

Timebanking in its many variations is powerful, says Rearick, because “it just feels very different to engage in economic life as equals and peers with everyone else. That's one of the reasons I'm such a zealot about timebanking. It's an experiential learning tool that helps you learn how the money economy is fake, and the real value is all the people around you. Dollars are something that cheapen that, in my view.”

For Rearick, Mutual Aid Networks have core principles of inclusiveness, beyond political ideology, in recognizing that everyone has passions and skills that can be put to good use for everyone. Mutual aid is about reciprocity, respect, democratic member control, and voluntary and open membership, among other principles.

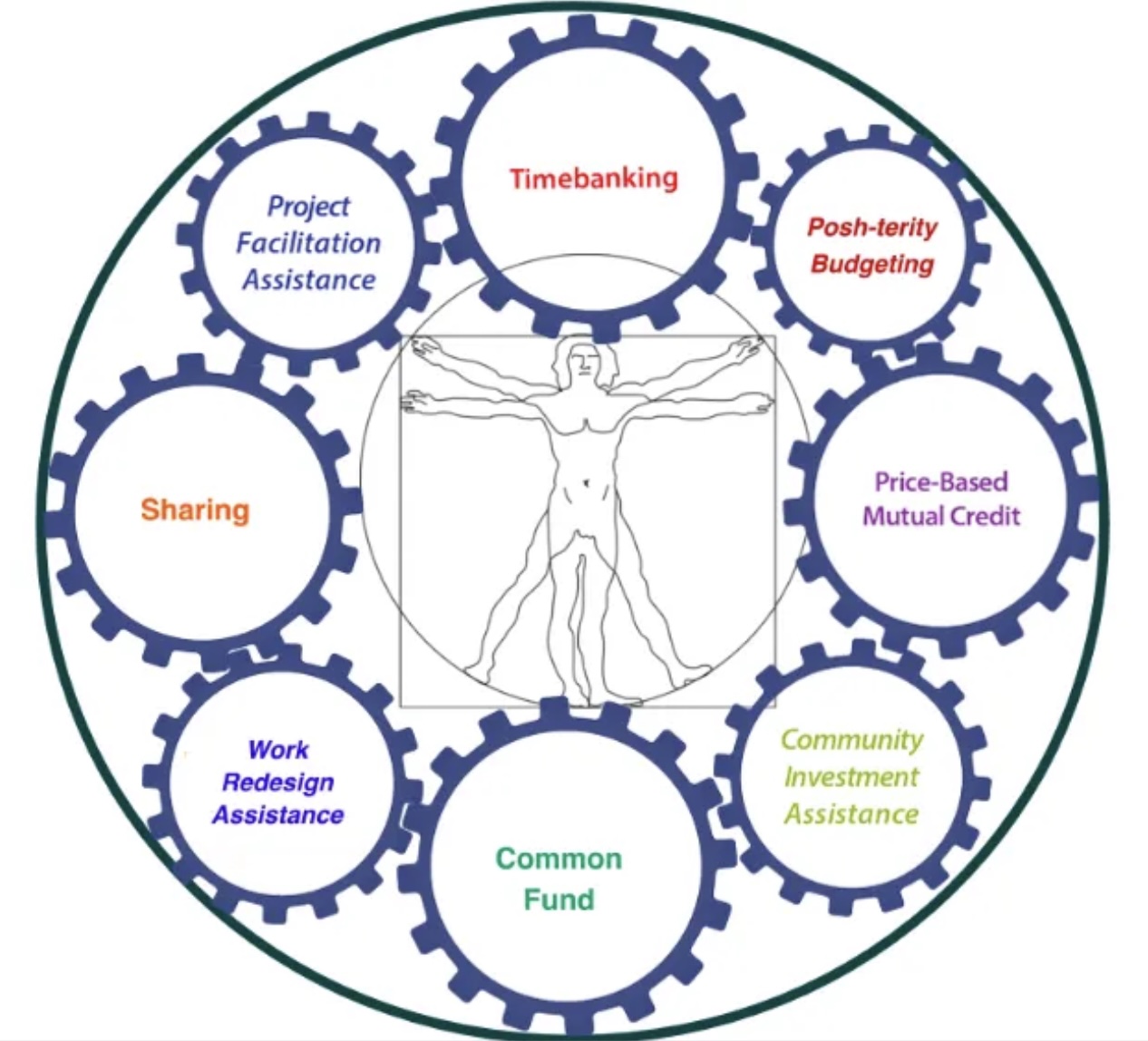

Mutual aid systems vary immense across the globe, but they constitute a robust network of players interested in the “real wealth” of social connections. Rearick’s Mutual Aid Network has its own PeerTube channel of videos, and it collaborates internationally to learn of innovative project approaches and to develop software platforms to support mutual aid.

You can listen to my interview with Stephanie Rearick here.

Recent comments