Toward Socio-ecological Markets

This is the fourth section of an essay, "Relationalized Finance for Generative Living Systems and Bioregions," by David Bollier and Natasha Hulst. The remaining section will be published tomorrow. The full essay can be downloaded as a PDF here. Previous sections appeared in sequence immediately before this one, at these links: Section 1. Introduction & Reframing the Economy Around Bioregioning; 2. Commons as Relational Provisioning and Governance; and 3. Toward a New Theory of Value (and Meaning): Living Systems as Generative.

4. Toward Socio-ecological Markets

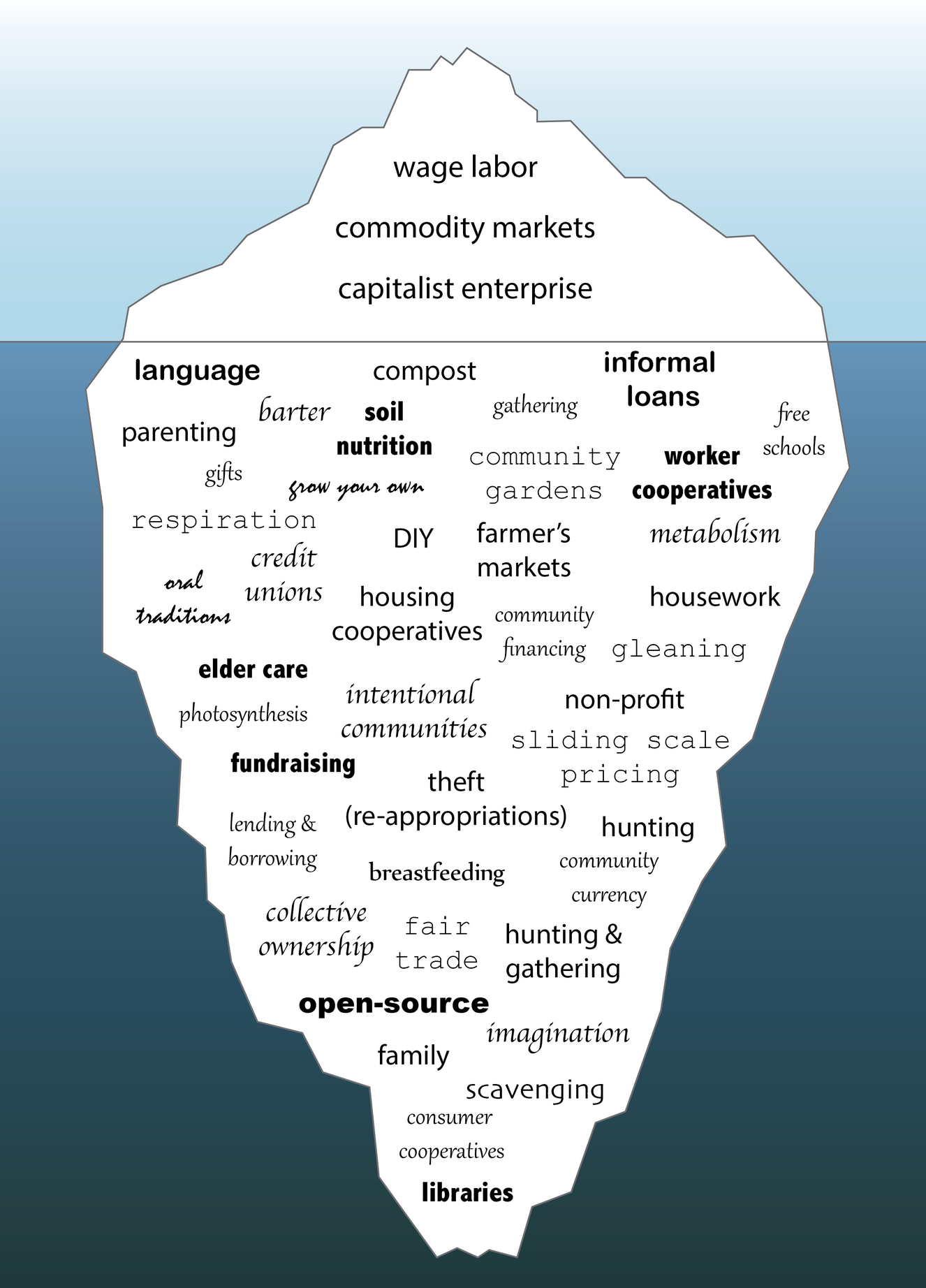

If bioregions are going to become more economically self-reliant and culturally self-directed, they must be able to insulate themselves from the neocolonial workings of global finance and markets. This means that bioregions must be able to assert their own investment priorities and become more self-reliant by intensifying their intra-regional commerce. Their basic challenge is to fend off outside commercial control and extraction (while obviously continuing many commercial dealings) so that the regional economy can benefit from the “multiplier effect” of locally circulated money while ensuring strong ecological stewardship and regional identity and culture.

Without some deliberate strategies for consolidating market activity within bioregions – making enterprises more interdependent and regionally focused – the priorities of capitalist businesses and global capital will override regional eco-stewardship and self-determination. Attempts to build a coherent regional economy and identity will be subordinated to “free market” imperatives and everything they privilege

It is impossible to prescribe a single strategic template for addressing these issues, however. An agenda this broad, ambitious, and long-term will necessarily vary from one bioregion to another. That said, in conjunction with commons, bioregional market structures and strategies could prod commerce to become more place-committed and socially embedded. These bioregional strategies include:

A. Community-designed infrastructures for bioregional production. Community participation in creating and managing small, shared infrastructures can be catalytic for the bioregional economy in general (commercial, commons-based, social, ecological). Shared bioregional infrastructures can reduce overhead, transport, and retail costs. It can make essential services like WiFi access, solar energy, water systems, grain milling, information-sharing, and databases -- more accessible and shareable, all while strengthening social cohesion and bioregional identity.

B. Inalienable shared assets. Assuring that major bioregional assets like arable land, groundwater, housing, forests, and other “natural assets” remain inalienable – off-limits in perpetuity to private purchase – makes a bioregion more stable and secure. It prevents companies and private equity funds from acquiring essential infrastructure through which they would extract exorbitant rents, siphoning money away from the bioregion. Keeping shared assets inalienable also addresses social inequity by making essential equity assets free or lower-cost, and available in perpetuity. For example, groups like Agrarian Trust (US) and Terre de Liens (France) rely on community land trusts to make land inalienable and stewarded as commons, which has all sorts of salutary effects: farmland for a younger generation of farmers, reduced equity costs that enable organic, local agriculture, and meaningful long-term employment for local residents.

- Read more about Toward Socio-ecological Markets

- Log in or register to post comments

Recent comments