This is the third section of an essay, "Relationalized Finance for Generative Living Systems and Bioregions," by David Bollier and Natasha Hulst. The remaining two sections will be published tomorrow and Saturday. The full essay can be downloaded as a PDF here.

3. Toward a New Theory of Value (and Meaning)

In rethinking how “nature finance” should be structured, the distinctive modes of value-creation in commons and bounded markets are often misunderstood. Standard economics sees market exchange, money and growth as the only significant engines of wealth-creation, a process that finance purports to facilitate. It is therefore difficult for conventional finance to understand that there are many other distinctive species of “value” that ecosystems and organized commoning generate.

The word “value” brings to mind money and markets, but the value generated by nature is quite different in an ontological sense. The bounty brought by rainfall, fertile soil, and biodiversity cannot truly be expressed through quantitative proxies, prices, algorithms, or markets because this “wealth” doesn’t exist in static, objectified forms or essentialist identities. Humans may equate fish with food and trees with lumber, but of course fish and trees play many other ecological roles in sustaining life.[12] The value of living entities subsists within their symbiotic relations – the dense web of interdependencies that generates abundance in a robust, self-sustaining system. This matrix is far more complicated than standard economics or markets can begin to represent.

While it’s possible to see abundance in objectified units (a bushel of apples, a hectare of land), the reality is that this value arises only as part of dynamic, evolving living systems whose actual value eludes quantification and monetization.[13]It may take “thirty leaves to make the apple,” as Thich Nhat Hanh wrote, but businesses, fixated on the marketable fruit, have only a narrow, economic self-interest in the leaves, roots, tree trunk, orchard, ecosystem, and weather.

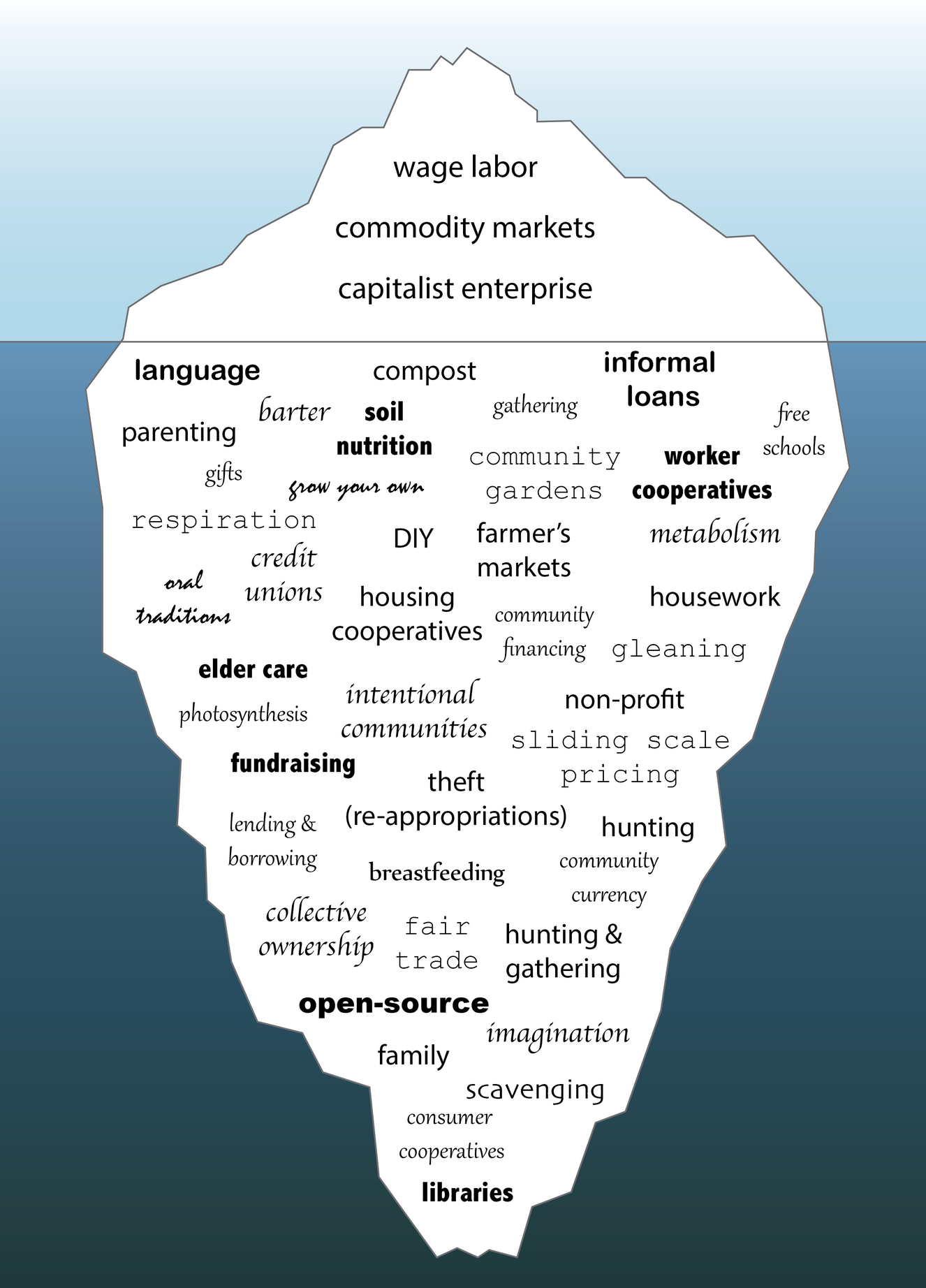

Inspired by feminist economic theory, J.K. Gibson-Graham proposed an iceberg image to suggest how much of “the economy” actually subsists outside of formal markets, remaining largely invisible and treated as inconsequential. The behaviors enumerated by the illustration below suggest how much economic work takes place in non-monetized forms, outside of wage labor and production for capitalist markets. These robust circuits of value-creation, often marginalized by standard economics and finance, can be seen in the generativity of living systems with sufficient organization: ecosystems of diverse organisms, agroecological farming, permaculture practices, online communities of collaboration, mutual aid networks, gift economies such as blood banks, scholarly disciplines, and artistic circles, timebanking collectives, and so on. Their contribution to “the economy” is enormous, but it is typically understated or ignored.

How does value arise outside of market exchange? It emerges as individual organisms negotiate forms of interdependence across species and constitutive differences. What results over time are creative, hybrid systems whose benefits can be freely shared. Biologist Lynn Margulis famously explained how autopoiesis and symbiotic relationships at the cellular level -- among various bacteria, for example -- are fertile, creative evolutionary forces.[14] The cosmologies of Indigenous peoples have long recognized this idea, that a meshwork of natural living relationships – human and more-than-human – can yield stable, sustainable forms of abundance. Indeed, there is a burgeoning literature these days documenting the deep entanglement of life-forms at myriad levels, and describing how this interrelationality makes life and indeed, human economies, possible.[15]

What’s crucial in any human economy, therefore, is respecting the integrity of the collective entanglements and unfolding of life, and learning to steward and care for it. This process integrates ecological dynamics with culture, and is essential to bioregional restoration and protection. Commoning -- the self-organized relations of living subjects, whether human or more-than-human – is an important way to protect these circuits of (material, enlivening, naturally expansive) value-creation.

However, modern economies have become so habituated to distilling human and ecological value into prices and property (marketable “resources”) that we rarely see the reductionist violence that it entails. Price distorts and limits our very understanding of value. It blinds us to the complicated generative dynamics of living systems. Indeed, price invites us to see many things as valueless. It commodifies living phenomena that in their natural state are dynamic, relational, subtle, and alive with their own creative agency.[16] While most people intuitively recognize that many forms of value exist outside of market economics, price remains the default tool for valuation.

Indeed, economists and politicians assume that if only we could make other forms of value visible – meaning, measurable and quantifiable – then the “free market” will be able to work its magic and properly assign an accurate value (price) to everything. This is a classic category mistake – the ontological error of ascribing a trait to something that it cannot possibly possess. Ecological dynamics cannot be expressed through money, property, or finance. Economics has contrived this fiction to normalize the idea of business incorporating waterways, forests, soil fertility, biodiversity, and much else into capitalist, anthropocentric logics.[17]

The power of price as a cultural category is perhaps related to its role in valorizing exchange value -- and implicitly ignoring use value and intrinsic value. Investor Warren Buffett has insightfully noted: “Price is what you pay; value is what you get.” In other words, even though price is treated as a statement of value, in fact “value” has an existentially richer, separate life of its own. It has subjective and social (intersubjective) dimensions that even the term “value” cannot quite encompass. Living organisms have experiences that yield a sense of meaning (biosemiotics is the subdiscipline), relational regularities (a sense of “belonging”), and a desire for flourishing and wholeness.

It’s worth noting that this understanding of “living value” differs from that of “systems thinking,” which sees planetary dynamics as systems that humans can in principle understand and master. This framing reflects Newtonian, mechanistic thinking: “If only we humans could deploy science and technologies to become “Master Engineers of Space Ship Earth”! (Bruno Latour’s term). It is more apt, indeed necessary, to see our earthly systems as Gaia – a living personality that has its own creative agency, history, and unfathomable, interconnected dynamics. This insight forces us to realize: Humanity is not separate from the Earth. We must recognize this fact and learn to become a humble, attentive partner working with the planetary organism in which we are embedded. At this point in our planet’s history, this is not a discretionary choice, but a necessity. In response to the abuses inflicted by our modern, capitalist civilization, Gaia is now aggressively, indifferently intruding on human societies as a political actor in its own right. Our challenge is not to double-down on modernity to “change nature” as if human agency could reign supreme. It is to recognize that Gaia is a living system that is far beyond our potential ability to control; respectful collaboration is essential.[18]

As Indigenous peoples have long understood, we must enter into the indirect reciprocity of gift-exchange with Gaia, a process that Lewis Hyde astutely describes in his classic book, The Gift.[19] He notes that the regenerative properties of life and nature will continue to generate their fruits (“value”) only so long as the gift ethic is honored and precious treasures are kept in circulation. (“The gift must always move.”) Once gifts are hoarded as capital and withdrawn from the circuits of gift exchange, creative yields decline and ultimately die.[20] This is a pertinent fable for our time of ruinous overextraction of fish, groundwater, timber, and every other earthly resource (the “tragedy of the market”). Bioregionalism invites us to recover and revere the “invisible economy” of relationality.

Will Ruddick, the founder of Grassroots Economics in Kenya, said that he’s encountered “more than forty-two different tribal names for traditions of social reciprocity,” such as people helping their neighbors harvest annual crops, build houses, or teach their children – all of which is maintained by people keeping informal track of everyone’s contributions and obligations. “Surprisingly,” Ruddick writes, “if you look through anthropology research, this social practice is almost undocumented, even though it seems to have been nearly everywhere.”[21] It petered out around the time of colonialism, when conquering nations introduced their own currencies, markets, and market culture. A local saying of the time held that “those who would lose their traditions become slaves” – an insightful description of what happens when colonial currencies and market wages supplant homegrown traditions of mutual aid. The currency and markets imposes a new regime of “value” on people.

To be sure, physical materials and relational life cannot be cleanly separated from each other. But in modern economies, we have not really resolved how to integrate each with the other without enshrining capital interests as the superior, organizing matrix of power and epistemic order.

Economic anthropologist Karl Polanyi sheds light on this issue in his classic history, The Great Transformation, which describes how capitalist markets in the sixteenth century began to supplant a system of commons, with markets eventually becoming the hegemonic ordering system for modern societies.[22] He explains how early capitalist markets created “fictional commodities” of land, labor, and money in order to annex them into its cosmological framework. The three realms are not in fact commodities because they pre-existed markets (land, labor) or derive their value from social exchange (money). The point is that capitalist businesses declared land, labor and money to be commodities. Early capitalism chose to objectify and monetize them in order to make them tradeable in markets. Predictably, the living character of these realms frequently clash with their ascribed status as “commodities” as workers assert their human needs, ecosystems deteriorate from extractive farming practices, and societies buckle under the demands made by capitalist currencies. Hence the persistent structural tensions between living systems and capital.

This brings us to the conundrum of financing for living systems today. Modern economies continue to misconstrue the value generated by living systems (local ecologies, academic disciplines, open source software communities, commons) by objectifying and monetizing them. So we have dueling ways of seeing them. We see them as living organisms AND financialized property, much as physicists have shown that light can manifest as either particle or wave. Living systems can be viewed through the prism of relationality as ecologists and Indigenous peoples do; but in modern capitalist societies, living systems are generally seen through the prism of price, as a commodity.

Relationalized finance is an attempt to candidly declare that there are other circuits of value-creation and meaning that have their own logics, outside of the market, that require their own forms of nourishment and protection. Property rights and financialization don’t acknowledge that living systems, as relational phenomena, may actually live on the “other side” of an ontological divide. Which raises a crucial question: Can the coherence and integrity of symbiotic living relations be maintained on their own ontological terms, or will investors, corporations and the state continue to misconstrue and enclose (privatize, commodify, sell) them, often in the name of helping and protecting them? Section 5 explores how finance and living systems – two classes of value (if that’s an appropriate term for living systems) might “play nicely together.”

For now, it’s important to stress that capital accumulation is not the point of commons. The goal is to fortify relational strategies for systemic and individual well-being. The goal is to strengthen social and ecological (and even cosmic) meaning. Indigenous cultures are renowned for their commitment to these realities. The problem for we moderns is to develop a discourse and vocabulary that will let us see and understand relational dynamics,[23] much as physicists have had to move beyond the language of Newtonian physics to understand the relationality of quantum mechanics. The social and ecological dynamics of living systems cannot truly be understood through numbers and financial sums; they must be articulated and expressed in nonmonetized, nonfinancial terms.

Community forests in India flourish through the affective labor of villagers working together. Villagers love and care for their forests, and community culture flourishes because people share responsibility for tending the forest, allocating wood and fruit, and scaring off poachers. Their affective stewardship (and stinted market sales) acts to conserve the forest while serving household needs.[24] In similar fashion, open source software communities thrive as more people coordinate their contributions to produce high-quality working code. “Many eyeballs tame complexity” and “the grass grows taller when it’s grazed on,” are two aphorisms of early open source hackers, attesting to the relational ethic and how it produces value.[25]

The primary problem in commons is not managing scarcity through price, as economics states; the task is to align living forces into shared purpose and create structures and cultures that can generate abundance and protect it. Permaculture expert Joline Blais explains how this works in natural landscapes through self-organizing “catchment” areas that bring together synergistic flows of energy -- “permaculture’s alternative to capital.” Blais writes:

Where capital is centralized accumulation that resists redistribution, catchment is a system for accumulating a critical mass of a needed resource, like water or soil minerals, in order to trigger self-organizing system, i.e. life forms, that then spread over the landscape. Some natural examples of catchment include the sun, plant carbohydrates, bodies of water, geothermal energy, and plate tectonics.

How does catchment work? Since the ‘driving force behind all natural systems’ is energy, catchment focuses on ways to capture naturally occurring flows of energy in such a way as to maximize the yield over time and space. As we know, entropy is the natural tendency to disorder, but it is balanced by an opposing tendency toward self-organization – or what we call life. This kind of self-organization happens ‘whenever energy flows are sufficient to generate storages.’

If the metaphor of capitalism is building a pyramid on the desert, the metaphor of catchment is growing a forest from the desert. In his film Planting in Drylands, Bill Mollison [the permaculture pioneer] shows a small rolling device that forms tiny divots over the desert floor. These small depressions in an otherwise flat surface collect dew and stray seed, so that over a surprisingly short amount of time, small sprouts shoot up, which in turn are able to collect more dew and hold more water in the soil. Under the right conditions, this positive feedback loop can actually turn a desert path to a living one with minimal human intervention – not even the need to sow seeds. Whether the result is a grassland or forest, the terrain moves from a handful of green spots to a terrain so evenly covered with life that it is no longer possible to find the spots where the wealth was initially concentrated.[26]

One might say that ecological and human-assisted commons (and potentially, bioregions) amount to “catchment areas” for organizing flows of energy, co-creativity, and biophysical matter. They bring people and other living entities into shared purpose to generate needed outputs and allocate benefits in fair, transparent ways. They nourish life. Commons eschew the organizing logic of capital and prioritize the instincts, needs, and creative agency of living systems, aligning individual, collective, and ecological needs together.

“Unlike capital, whose increase is measured only in financial terms, catchment wealth is measured in terms of real wealth,” notes Blais. “It replaces short-term, centralized profit with long-term asset building for the benefit of future generations.” In nature, for example, the “real wealth” assets are “soil fertility, seed saving, reforestation, key line water harvesting, and carbon, water and nutrient storage in the landscape,” Blais writes. The beauty of real wealth, she continues, is that it is self-maintaining, depreciates slowly, uses simple technologies and processes, and resists monopolization, theft, and violence. Stabilized by such real wealth, commons provide long-term security and protection from enclosures.

Commons in modern life pose a conundrum for capitalist finance and state policy, however. Even though commons generate enormous, diverse streams of value – social, personal, ecological, economic – most of it is not easily propertized or monetized. Indeed, introducing private property rights, market transactions and individualism into a commons can destroy its generativity as a catchment zone. For example, the vitality and cachet of Couchsurfing, the hospitality gift-exchange for travelers, dissipated after venture capitalists bought the website and converted it into a paid travel service. Similarly, open source software networks are often fractured when money is introduced into a community of cooperating peers. A research community that flourishes by sharing its knowledge can be crippled if some of its members patent collectively developed insights for private gain.

How, then, can the special value-generating dynamics of commons be protected and nourished within a capitalist system that has a very different worldview and priorities? Can the ontological norms of conventional finance build respectful interfaces with the intersubjective, relational norms of commons and ecosystems?

NOTES

[12] Data and numbers can yield useful information, of course, but they cannot represent the complex, subjective relational ontology of living systems. That is the nub of the problem for conventional finance.

[13] See Sian Sullivan website, “The Natural Capital Myth and Other Stories,” at https://the-natural-capital-myth.net. Sullivan describes numerous business efforts to redefine the value of nature in market-friendly, ecologically problematic terms.

[14] James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis co-developed this theory in the 1970s. See “Gaia Hypothesis” entry, Wikipedia, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaia_hypothesis. On the power of relationality in commons, see Andreas Weber, Being and Desire (Chelsea Green, 2018) and “Sharing Life: The Ecopolitics of Reciprocity” (Heinrich Boell Foundation, September 2020), at https://in.boell.org/en/2020/09/10/sharing-life-ecopolitics-reciprocity.

[15] Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Milkweed Editions, 2013); Merlin Sheldrake. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures (Random House, 2021); Peter Wohlleben. The Secret Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate — Discoveries from a Secret World (Greystone, 2016); Suzanne Simard. Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (Vintage, 2022); Eduardo Kohn. How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the Human (University of California Press, 2013); Wahinkpe Topa and Darcia Navaez, Restoring the Kinship Worldview: Indigenous Voices Introduce 28 Precepts for Rebalancing Life on Planet Earth (North Atlantic Books, 2022); Vanessa Marchado de Oliveira, Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism (North Atlantic Books, 2021); Yuria Celidwen, Flourishing Kin: Indigenous Wisdom for Collective Well-Being (Sounds True, 2024); Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World (HarperOne, 2020); Andreas Weber, Enlivenment: Towards a Fundamental Shift in the Concepts of Nature, Culture and Politics (Heinrich Boell Foundation, 2014); and Matter and Desire: An Erotic Ecology (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017).

[16] This theme is extensively explored in Adrienne Buller, The Value of a Whale: On the Illusions of Green Capitalism (Manchester University Press, 2022).

[17] A similar fallacy is the idea that aggregating “small initiatives” into larger bundles will make them “investable,” thus enabling capitalist investment to provide market-driven solutions to environmental problems. This fiction encourages us to adapt the living world to conform to financial logic, rather than the reverse: devising new types of finance to honor the living dynamics of natural systems.

[18] Philosopher Isabelle Stengers and Bruno Latour note that Gaia is intruding on the nation-state and human affairs as an unacknowledged political player in its own right. Latour notes that “nature” has historically been seen as indifferent, impartial and causally regular, but now, more properly seen as Gaia, is revealed as an assemblage of “living organisms that are capable of playing a role in the local history of the Earth….Far from being disinterested with respect to our actions, it now has interests in ours. Gaia is indeed a third party in all of our conflicts….” See Stengers, In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism (Open Humanities Press and Meson Press, 2015), Chapter 4; and Latour, translated by Catherine Porter, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime (Polity, 2015), p. 238.

[19] Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property (Vintage, 1979).

[20] Capitalist finance is constantly trying to privatize and marketize its relationships with nature, with the blessings and empowerment of law. Examples include patents for genes and lifeforms; financial instruments that securitize flows of natural resources like water, fish, and timber; payments for the use of “ecosystem services”; and the REDD program [Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation].

[21] David Bollier, “Will Ruddick on ‘Commitment Pooling’ to Build Economic Commons” (March 1, 2024), at https://www.bollier.org/blog/will-ruddick-commitment-pooling-build-econo...

[22] Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Beacon Press, 1944/1957).

[23] David Bollier and Silke Helfrich, Free, Fair and Alive: The Insurgent Power of the Commons (New Society Publishers, 2019), Chapters 2 and 3, at https://freefairandalive.org/read-it/#2 and https://freefairandalive.org/read-it/#3.

[24] Neera Singh, “The affective labor of growing forests and the becoming of environmental subjects: Rethinking environmenrtality in Odisha, India,” Geoforum 47 (2013) 189-198.

[25] Eric Raymond, “The Cathedral and the Bazaar,” at http://www.catb.org/~esr/writings/cathedral-bazaar/cathedral-bazaar/inde....

[26] Joline Blais, “Indigenous Domain: Pilgrim, Permaculture and Perl,” Intelligent Agent, 2006, at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 299460968_Indigenous_Domain_Pilgrim_Permaculture_and_Perl. Blais sees the idea of generative catchment areas as relevant to living systems in diverse realms. In her essay, she focuses on Indigenous cultures, permaculture, and open source software.

Recent comments