In the course of researching his forthcoming book on human cooperation, Humankind: A Hopeful History, Dutch historian Rutger Bregman had to deal with the inevitable atrocities and behaviors that suggest that humanity is barbaric at its core. There is no question that humanity has shown such tendencies through history. But is savage cruelty the default setting for “human nature”?

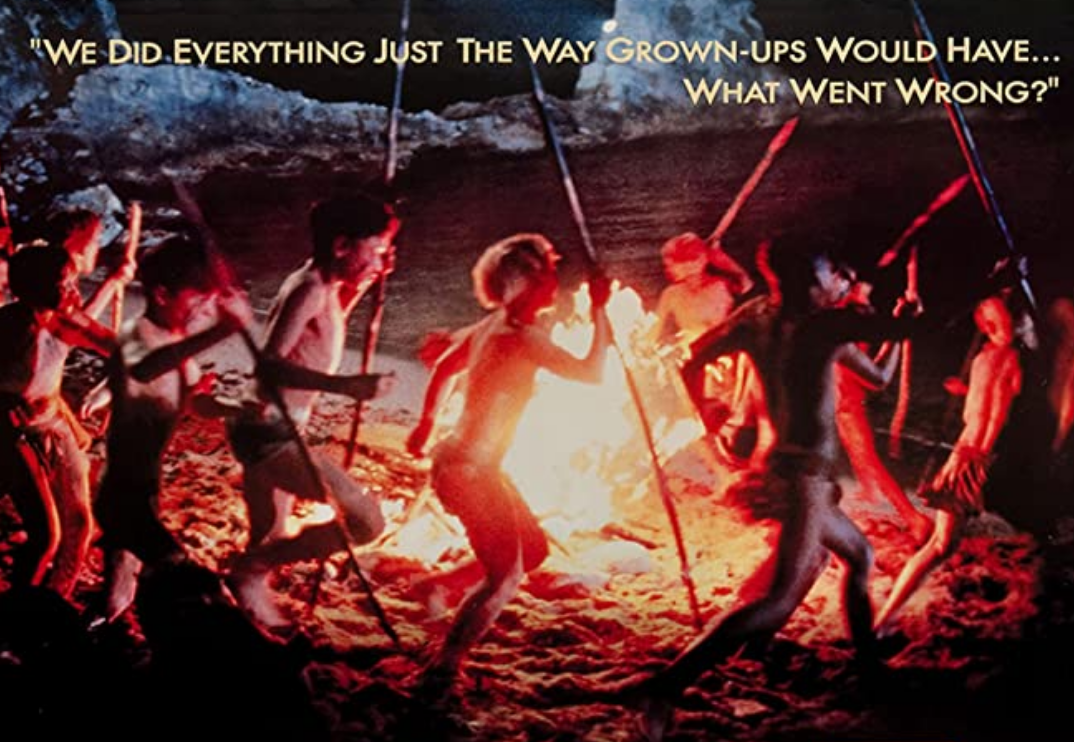

As anyone who has gone through high school remembers, that is the one lesson we were all taught when assigned to read Lord of the Flies, by William Golding. That classic book, you may recall, is about a band of British schoolboys who are shipwrecked on a desert island. Forced to create their own society, they end up shedding the veneer of (British) civilization and reveal themselves to be utterly nasty and depraved. When the constraints of civilization and state power disappear, the story tells us, we all revert to savagery. We choose barbarism.

Since its publication in 1951, Lord of the Flies has been translated into more than 30 languages and sold tens of millions of copies. The idea that humanity is disturbingly sinister at heart would seem to be widely believed. Or at least readers may find such stories darkly thrilling, for which there is certainly something to be said.

But Bregman discovered that Lord of the Flies was more a flight of William Golding’s perfervid imagination than an empirical description of humanity. In researching his book, Bregman tripped across a blog post that referred to an actual incident of shipwrecked boys in the South Pacific in 1965. According to the blog, “six boys set out from Tonga on a fishing trip….Caught in a huge storm, the boys were shipwrecked on a deserted island. What do they do, this little tribe? They made a pact never to quarrel.”

Whaaaaaat? You mean, boys stranded in the wilderness don’t descend into barbarism?

In a recent piece in The Guardian, Bregman recounts his research odyssey to confirm the incident and learn more details. (See, also, a profile of Bregman here.)

It turns out that the Australian boys had been stranded alone on the island of Ata for fifteen months before being rescued on September 11, 1966. Fifty years later, Bregman flew to Australia to try to track down any survivors of the incident. He located sea captain Peter Warner, then 90 years old, who told Bregman how he came to rescue the lost boys given up for dead.

The island on which the boys were marooned had been inhabited until 1863, when a slave ship captured all the natives and sailed away. While steering his ship past Ata, Captain Warner noticed a fire. Looking through his binoculars, he saw naked boys screaming for help. The six boys were all Catholic schoolboys, ranging in age from 13 to 16, who had drifted for six days without food or water following a big storm. Eventually they washed up on the shores of Ata.

The fifteen months stranded on the island did not resemble the story of Lord of the Flies, however. As Captain Warner recalled in his memoirs, “the boys had set up a small commune with food garden, hollowed-out tree trunks to store rainwater, a gymnasium with curious weights, a badminton court, chicken pens and a permanent fire, all from handiwork, an old knife blade and much determination.” The boys survived on fish, coconuts and tame birds, and seabird eggs, wild taro, bananas and wild chickens.

In Lord of the Flies, the boys got into fights about who would maintain a fire to alert would-be rescuers. But the boys on Ata assiduously kept their fire going for more than a year. The boys had a roster for tasks, which they did in pairs. If arguments erupted, they agreed to a time-out. Bregman writes that “their days began and ended with song and prayer.”

The real-life drama of the stranded boys of Ata helps us to see that we invent the stories we want to believe. Who knows what motivated William Golding to tell this story, but Bregman notes that Golding as a person was apparently unhappy, alcoholic, and prone to depression. Golding himself even acknowledged Nazi-like tendencies in himself.

It may have been that Golding wanted to channel the spirit of Thomas Hobbes, the political philosopher whose fable about social contracts has long been used to justify state power. A Hobbsean story like Lord of the Flies helps justify our supposed need for the modern, coercive state. Who else, after all, is going to keep order when we individually can’t constrain our own savagery? Lord of the Flies in effect dismisses the idea that we might self-organize a stable, humane order that can satisfy our needs.

Bregman’s discovery of the stranded boys of Ata is therefore a revelation. It helps debunk the fictionalized projections about humanity that often pass for political wisdom.

I’d argue that the story of the shipwrecked boys validates a different story about humanity. It affirms the reality and potential of commoning. As Bregman puts it, “It’s time we told a different kind of story. The real Lord of the Flies is a tale of friendship and loyalty; one that illustrates how much stronger we are if we can lean on each other.”

Recent comments