This is the fifth and final section of an essay, "Relationalized Finance for Generative Living Systems and Bioregions," by David Bollier and Natasha Hulst. The full essay can be downloaded as a PDF here and at Natasha Hulst's Substack. Previous sections appeared in sequence immediately before this one, at these links: Section 1. Introduction & Reframing the Economy Around Bioregioning; 2. Commons as Relational Provisioning and Governance; 3. Toward a New Theory of Value (and Meaning): Living Systems as Generative; and 4. Toward Socio-ecological Markets.

5. Relationalized Finance: Bridging the Chasm

As should be clear by now, the core puzzle that relationalized finance seeks to mitigate or resolve is actually an ontological and cosmological clash that takes place in everyday circumstances. It’s a struggle between different notions of value and meaning. It’s the glimmer of a worldview that steps away from many premises of liberal-capitalist-modernity. Does humanity consist chiefly of rational, self-interested individuals seeking material gain through market exchange, and exploiting nature as a (dwindling) resource that stands separate and apart from humans? This is the cosmology of contemporary finance.

Or does humanity consist of interdependent, cooperative individuals nested within collectives, which themselves are nested in complicated ways within an animate Earth of countless living beings engaged in a symbiotic, evolutionary dance? We need a finance in sync with this world.

Without some adaptation of conventional finance and its implicit cosmology, capitalist finance will continue to inflict harm on nature and communities. It will continue to financialize life-systems as assets, and in so doing, superimpose an alien matrix of value and extractive production on them. So a key goal here is to help commoners secure much greater equity and control over their shared wealth, and to help them avoid becoming beholden to distant investors, lenders, and state authorities with their own empire-building priorities.

What might a relationalized finance regime look like? It would be one version of a Bioregional Finance Facility (BFF), a breakthrough idea introduced by Samantha Power and Leon Seefeld in their pioneering book of that title.[40] A BFF is intended as a kind of bridge between the current finance paradigm and an ecologically minded economy on a bioregional scale. How exactly a BFF should be structured and managed remains something of an open question because there are so many practical challenges, if only because bioregions themselves are so varied.

We conclude, however, that there are deep tensions between conventional and progressive finance on the one hand, and the aspirations to protect and restore bioregions on the other hand. Modern finance cannot really comprehend nonpropertized, nonmonetized forms of value unless they are properly “coded” in dollars, numbers, and units of property. So to make investment or lending intelligible, the ontological realities of generative living systems – its value and meaning proposition – are de-natured and misrepresented.

Hence the conundrum: Dominant forms of finance tend to stymie or co-opt novel, emergent alternatives, casting them as impractical and marginal. And yet building effective alternatives that might render the current models obsolete (the R. Buckminster Fuller admonition[41]) has its own serious liabilities – a logic that conventional investors and lenders reject and a social coherence that is embryonic and culturally invisible to mainstream players, which of course limits the capacity of novel alternatives to grow.

Given the dismal history of “green finance” models in redirecting capital and catalyzing transformation (see p. 1 of essay), we believe the clear necessity is to create novel alternatives that can tap into social and local energies (commoning, cooperation, bioregioning) and grow viable new forms of finance in tandem with these movements. Bioregional players need the ability to borrow and receive “transvestment” from capitalist circuits of value, in order to establish stable new regimes of care, reciprocity, cooperation, and bioregional coherence.

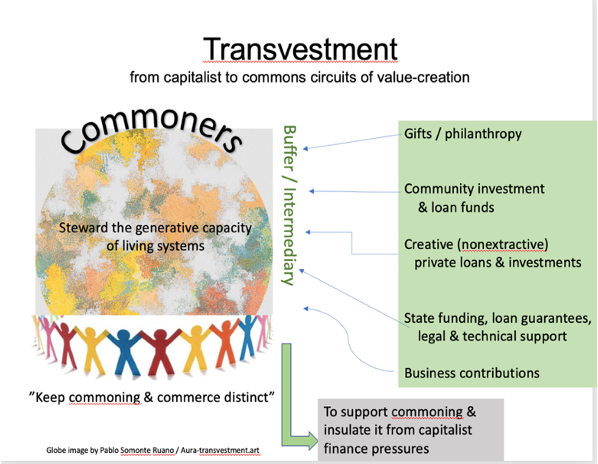

We therefore propose a relationalized finance system that is able to direct funds to commoning and socio-ecological markets that work as stewards of generative living systems. To overcome the ontological clash of finance and ecosystems, we propose a simple but versatile entity that would serve as a buffer, or intermediary, between finance and commons. The buffer entity – a type of BFF that, in this instance would be a “regrantor group” -- would mitigate or neutralize the extractive ambitions of capital investment and lending so that funds would flow to stewards of the generative value of living systems.

The chart below illustrates a general scenario. Commoners, through their affective labor and care for a body of shared wealth (land, water, farms, buildings, parks, etc.), would act as stewards of living value. And businesses that agree to participate in quasi-bounded, stinted bioregional markets would have access to capital and lending. Under this scheme, a transfer of money is much more than a money-making transaction; it is an affirmation of the recipients’ shared commitments to commoning, bioregional markets, and the alternative theory of value (living systems as generative in nonmonetized, nonpropertized ways).

Money would flow through a “regrantor fund” that pools money from commoners themselves, friends and allies, and adjacent movements, augmented by money from crowdfunding, supportive businesses, philanthropies, and community foundations. The state, especially municipal and regional governments, could be potentially important sources of additional funding because their ostensible purpose is to protect and advance the common wealth (in all its forms, not just market value).

The regrantor fund would act as an independent, non-governmental buffer/intermediary, standing between funding sources and the commons. Its role would be to act as a central collector of funds to support bioregional work (a BFF), especially via commons, and to neutralize any direct, transactional demands on funding recipients.

Since the elders of the Commonsverse and bioregional community would be the trustees of the regrantor fund, the fund would be a vehicle for noncapitalist practitioners to exercise autonomous judgment and leadership, in resonance with peers to whom they are accountable. The larger terms of governance (how appointments are made, funding criteria, performance requirements, etc.) deserve more discussion, but in any instance would reflect local priorities, aspirations, and needs.

The idea of a regrantor fund is inspired by the many foundations associated with free and open source software projects, especially for software that is essential for the Internet and computer operating systems (GNU/Linux, Debian, Apache, Perl, etc.). These foundations typically accept funds from various donors (including Big Tech companies) to support their commoning to produce non-proprietary, shareable software. The foundations, governed by respected community practitioners, act as intermediaries to prevent transactional “purchases” of the community’s talents and to advance the community’s key priorities and projects.

The foundation-as-intermediary model upholds an essential pattern of commoning -- to “keep commoning and commerce distinct.”[42] This rule helps prevent business opportunities or sudden inflows of money from disrupting the social solidarity of the group. Obviously, securing money is always a temptation and often useful, but no commons will succeed unless it first cultivates a strong, committed culture of commoning. Strong relationships of trust, a shared purpose and ethic, community rituals, and a good reputation are bulwarks against market enclosures.

Seen in this larger social context, it becomes clear that a regrantor fund is not merely be a financial institution. It is a force for propagating the social logics of bioregionalism. It would champion a different value-creation regime: the power of living, intersubjective human and more-than-human lifeforms working in concert, with carefully peer-regulated market relationships. In everyday parlance: the fund would foster eco-stewardship through commoning and bounded, stinted markets. The fund would make capital allocation and funding decisions (for new infrastructures, startup experiments, software platforms, operational needs, public engagement, etc.). It would also host deliberations about strategic interventions and initiate public outreach as part of its mission to champion a bioregional transition.

While the regrantor fund would function as a Bioregional Finance Facility (BFF), not all BFFs would necessary embrace the regrantor fund idea as a tool to support generative living systems and commons on their own ontological terms. Green finance, for example, might be content to channel existing pools of capital to generically defined “green” projects, without attempting an OntoShift in finance itself. And they would probably continue to demand private extraction of economic value (perhaps in lesser ways) and control management and production practices from the outside.

While we focus on the idea of a regrantor fund here, there are other notable examples for allocating money in democratic, participatory ways (rather than investors or philanthropies retaining that authority for themselves). The Chorus Foundation has empowered Anchor Organizations in four regions (Alaska, eastern Kentucky, Richmond, California, and Buffalo, NY) to allocate funds to support a “just transition” from fossil fuels, with an accent on democratic governance, participatory budgeting, relationship-building between geographies and grantees.[43] A related model is “flow funding,” which eschews grant applications and bureaucracy in favor of grantmaking through social collaboration and trusted relationships. The essential purpose of flow funding is to empower grassroots players in a given bioregional to allocate resources themselves, relying on their direct, grounded knowledge of their challenges, without the paperwork and delays that often characterize conventional philanthropy. This approach “accelerates real impact, strengthens local economies, and ensures resources go directly where they are most needed.”[44]

As climate collapse grows more proximate, the frequent justification for retaining basic forms of existing finance (and philanthropy) is that “we don’t have enough time” to instigate serious changes through bottom-up, cultural means. What matters most is making massive, rapid shifts of capital to fund eco-revitalization, goes the argument. These are powerful arguments so far as they go. But the disappointing performance of so many capitalist-facing finance schemes over the decades does not inspire confidence, which leads us to conclude that failing to revamp the foundational premises of capitalist finance has its own significant liabilities and risks. Can we dare not to develop a new genre of noncapitalist finance?

Another objection is that bioregional or local approaches are “too small” to make a difference quickly enough. But one can argue that large-scale “solutions” have their own problems associated with their very scale. The higher ROI requirements and efficiencies of large, centralized projects summarily preclude consideration of a whole class of distributed solutions at smaller-scales, which, given proper support, could leverage nonmarket community energies in cost-efficient ways. In addition, large-scale mono-solutions are brittle; their centralization and rigid design templates reduce resilience.

It’s important to add that decentralizing power and innovation to localities (“subsidiarity”) is an important way to fight authoritarian state power and empower democratic practice and norms. In short, the profitability thresholds for large corporate projects entail many disabilities of their own.

While novel forms of capitalist finance surely have a role (and indeed, they remain the dominant vector of eco-financial innovation), let’s admit that the future of nature finance is not a binary proposition – capitalist or noncapitalist? Rather, it’s a matter of dynamic coexistence. Economist Kojin Karatani has noted that world history may be best understood not through modes of production, but through its modes of exchange: the reciprocity of gifts (clan society), ruling and protection (state society), commodity exchange (industrial capitalist society), and a fourth and future one that transcends the other three.[45] Our point for this discussion: the different modes of exchange driving eco-finance are not mutually exclusive. They can coexist simultaneously, but in varying degrees. We believe relationalized finance animated by the gift ethic, open source-style cooperation, social solidarity, community loyalties, and other attributes of commoning have a far greater potential than conventional finance can understand.

So while relationalized finance will certainly not displace capitalist finance, it has the capacity to introduce a very different, catalytic logic that can have far-reaching ramifications and influence. The wager being made by relationalized finance is that it could begin to displace Old Finance with stabilizing, satisfying new forms that reflect a new, emerging worldview and set of social practices.

Relationalized finance represents a bet that the factors that Old Finance regards as peripheral, will in fact come together to bring forth a new value-paradigm and Ecocene forms of finance. Old Finance will continue to cling to its perceived (but waning) base of power, capital-centric logic, its functional efficacy as a legacy system, and its worldview. The point of relationalized finance is to herald and enact a new Ecocene finance that catalyzes power-shifts in ontology, personal values, social relations, provisioning practices, and cosmic beliefs. It would both reflect and animate a new order that will far transcend finance alone.

Our very categories of thinking will evolve and mutate. While contributions to a regrantor fund might be characterized as “donations” or “subsidies,” the point of relationalized finance is to give new cultural meanings to such flows of money. It is frankly difficult to say whether giving money to build a new bioregionally resilient civilization should be seen as a donation, an investment, social redistribution of wealth, or empowerment for commoners in building a new socio-ecological-economic order. It is all of the above. Perhaps the social utility of potlatch – the Indigenous practice of tribal chiefs giving away their wealth to tribal members in showy displays of redistribution – may be a relevant concept.

One thing is clear: In a world that still inhabits the cultural mindset of capitalist finance, new ways of thinking about finance as a socio-political and ecological phenomenon are needed. New logics and meanings will take time to emerge. There is always the danger that Old Finance will use any new thought-categories and language as performative in any case -- emotive guises that enable Old Finance to maintain the basic structures of finance without truly recognizing the ontological character of living systems.

For this reason, we believe it’s important to talk about the transvestment of money from capitalist-circuits of value (monetized, propertized) to commons-stewarded realms of value (relational biophysical life). Transvestment occurs when funds circulating in capitalist markets are given to the regrantor fund, and then allocated to well-vetted commons and businesses in loosely bounded bioregional markets.

The term transvestment underscores that the transfer of money is executing a serious shift in the value-paradigm and bio-material practices. The money is not simply pursuing return on investment; it represents a commitment to a new order of a different character, one that is simultaneously an investment, gamble, donation, and solidarity statement in a political/cultural sense. Transvestment is not simply capitalist investment and lending in a freshly named extraction zone. It is an affirmation of the generative value of a coherent, organically integrated living system.

This reframing and shift of meaning for money transfers are important because conventional eco-finance fails to acknowledge the OntoShift that bioregioning requires. For example, biodiversity credits and carbon-offsets do not truly recognize the particular value of particular places. They assert the fiction that ecological harm inflicted in one place can be compensated for somewhere else, as if one landscape was essentially equivalent to all others. This is the danger, too, of “payment for ecosystem services” (PES) and KPIs (“key performance indicators”), which monetize ecological “services” and convert them into tradeable commodities. In effect, natural biodiversity (or healthy waterways or forests) are reconceived as “resources” that can be bought and sold in eco-mitigation markets.[46]

The term transvestment signals that money from capitalist circuits of value is in fact being re-purposed. It is not a purchased token of ownership or services, but enabling support for commons-based stewardship of a specific place. By supporting “stewardship support agreements” or “commons stewardship funding” (as the transfer might be named), transvestment signals a break from the Old Finance paradigm. It pierces the veil of eco-finance charades by conceding that such schemes “run fundamentally in opposition to the cosmovisions of many Indigenous Peoples and other communities, who understand Nature as our mother, not as a commodity,” as an environmental coalition put it.[47]

A regrantor group functioning as a BFF could help commons develop themselves while nonetheless existing in a capitalist society. Transvestment could give eco-stewards the freedom to pioneer qualitatively new types of production, governance, and eco-relationships. For example, CSA farms would be able to produce organic crops for local households without the costly markups, herbicides, and marketing expenses of industrial agriculture. Coastal fishers would be more able to harvest fish within the carrying capacity of the regional fishery while still making a living from the work. Software programmers would be able to develop network protocols and apps that could be open source, shareable, and respectful of user privacy and social needs. There would be no financial pressure for programmers to design code that maximizes user screen-time via anti-social algorithms and privacy-invasive data-surveillance.

The criteria for distributing regrantor funds would require careful thought, however, because relationalized finance operates from some very different socio-economic and ontological premises than conventional finance. The risk models of conventional finance presume a stable society, regulatory institutions, and economic growth, and the heft of finance history supports the prioritizing of exchange-value and private profit. But in a world of unpredictable disruptions, ecological decline, and social unrest, the very parameters for investment are likely to change. It could well be that a well-organized bioregional space with a coherent web of commons and bounded-business relationships would be a safer long-term investment.

On the other hand, it could be that only a noncapitalist finance could support what commons treat as primary – care-work over productivity; meeting basic needs for all rather than catering to the most profitable market demand (for those who have the money); and conscientious long-term eco-stewardship over short-term financial performance. In any case, it’s clear that a single set of performance metrics and a single bottom-line are inapt ways of assessing investment. For a regrantor group with an agenda that blends finance, bioregional vitality, and social coherence, there are currently too many unknown, interconnected, floating variables. Metrics for value-generated may be more properly applied to the entire socio-ecological system than any single borrower or investment asset run by a commons or business enterprise.

That said, there are some useful and necessary tools for evaluating the performance of projects. Peer certification is a process that convenes respected players in a given community of practice, and asks them to assess the internal participation, coordination, communications, trust, and efficacy of the project. The City of Barcelona has a Community Balance peer certification system for evaluating local community organizations.[48] Many agroecological farmers use a locally focused peer certification system, known as the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS).[49] This system certifies the qualifications and practices of producers based on the judgments of active, known, and trusted participants in the community. One virtue of peer certification is that it allows situated judgments and nuanced discernments by practitioners themselves, rather than relying on somewhat artificial, abstract, rigid standards that cannot be reliably applied.

The City of Amsterdam is currently exploring the development of a relationalized finance system. Its office for cooperatives and citizen participation has hosted a number of workshops and public presentations on the topic.[50] In Kingston, New York, a group of ordinary citizens has developed a participatory community fund, Kingston Common Futures, whose funding grants are made by ordinary people, not local business and political elites.[51] There is wider interest in the promise of relationalized finance and other fascinating experiments in finance, but there is not yet a focused field of inquiry or coordinated movement to move the ideas forward.

* * *

This essay is an invitation to take action. We hope to advance this process, first, through further discussion and debate about relationalized finance, so we welcome your comments and suggestions at the email addresses below.

In time, we hope to convene a small working group to help develop the ideas of this memo in greater depth. New strategic initiatives and pilot projects should be launched in collaboration with venturesome partners. As feasible, we hope to collaborate with existing bioregional initiatives, activist networks, relocalization projects, and municipalities to explore how relationalized finance might be organized in their circumstances. We hope you agree that there are many promising paths for developing independent, noncapitalist forms of finance.

This reality is seemingly confirmed by the experimentation and energy already underway in bioregional spaces, albeit in quite disaggregated and diverse ways. New seed-forms urgently need attention, collaborators, and funds if they are going to address unfolding climate disruptions and related ecological and social crises. Moving forward effectively requires clarity about the limits of conventional finance – and the creation of new finance vehicles that honor the deep complexities of commoning and ecosystems at bioregional scales.

David Bollier

Reinventing the Commons Program

Schumacher Center for a New Economics

Natasha Hulst

Coordinator, Land Commons Initiatives in Europe

Schumacher Center for a New Economics

natashahulst@centerforneweconomics.org.

December 8, 2025

NOTES

[40] Samatha Power and Leon Seefeld, Bioregional Financing Facilities: Reimagining Finance to Regenerate Our Planet (Biofi Project, 2024) at https://www.biofi.earth.

[41] Fuller wrote: “To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

[42] David Bollier and Silke Helfrich, ˆFree, Fair and Alive: The Insurgent Power of the Commons (New Society Publishers, 2019), pp. 151-155.

[43] Ben Roberts et al. and r3.0, Blueprint 8: Funding Governance for Systemic Transformation: Allocating investment and grant-making for a regenerative and distributive economy, September 2, 2022. See esp. pp. 68-77.

[44] Kinship Earth, Flow Funding: A Collaborative, Trust-Based Model of Giving, at https://www.kinshipearth.org/flow-funding. See also Syd Harvey Griffin, “Bioregional Flow Funding Opens New Grassroots Possibilities,” February 12, 2025, at https://www.bioregionalearth.org/blog/flow-funding.

[45] Kojin Karatani, The Structure of World History: From Modes of Production to Modes of Exchange (Duke University Press, 2014).

[46] Fréderic Hache of the Green Finance Observatory skillfully dissects the fallacies of biodiversity offsets and credits in a report, noting, “These approaches fundamentally misunderstand the uniqueness and complexity of ecosystems, making the idea of substituting one ecosystem for another scientifically unsound and ethically questionable….[B]iodiversity credits are likely to be used almost entirely for offsetting rather than voluntary conservation, echoing the failures of carbon markets.” https://www.biodmarketwatch.info

[47] Civil Society Statement on Biodiversity Offsets and Credits, October 2025, at https://www.biodmarketwatch.info.

[48] Gregorio Turolla, “A Focus on Barcelona’s Community Balance,” URBACT, February 20, 2020, at https://urbact.eu/articles/focus-barcelonas-community-balance-protocol-g...

[49] IFOAM Organics International, at https://www.ifoam.bio/our-work/how/standards-certification/participatory...

[50] Natasha Hulst, Annelies van Herwijnen, and David Bollier, “Building a Finance System for Thriving Commons in Amsterdam,” April 2024, working report at https://openresearch.amsterdam/nl/page/109389/building-a-financial-ecosy...

Recent comments